Ticks in California

Soft Ticks (Family Argasidae)

Hard Ticks (Family Ixodidae)

Ticks are divided into two families, soft ticks and hard ticks. The two most common ticks found outdoors in the district are the Western Black-Legged Tick and the Pacific Coast Tick.

The only source of nutrition ticks use is the blood sucked from humans or other animals.

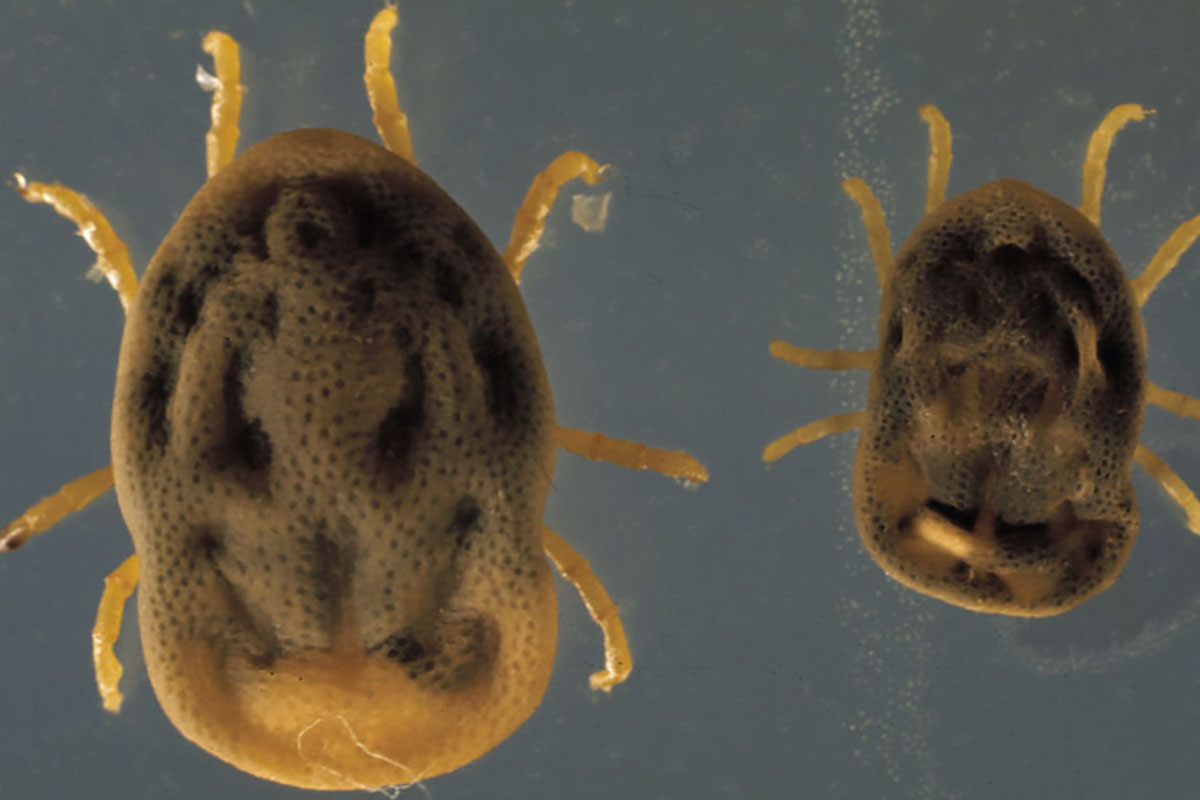

Ornithodorus coriaceus

Pajahuello Tick

Mat Pound, USDA Agricultural Research Service, Bugwood.org

Associated with coastal and sierra foothill habitats from San Diego to Humboldt county. Found in and around resting places of their large mammalian hosts (primarily deer and cattle).

This tick will readily take blood from almost any warm blooded mammal in the laboratory1. Humans may accidentally encounter this tick when they come in contact with host bedding sites, especially during activities such as hunting and camping.

Reaction to Bite

For humans, the bite of this tick is notoriously painful, resulting in a localized inflammatory response due to a toxic substance introduced into the bite site during feeding.

Otobius megnini

Spinose Ear Tick

Mat Pound, USDA Agricultural Research Service, Bugwood.org

Rarely, these ticks have been found on humans, dogs, cats, and sheep. Heavy infestations with this tick can result in intense irritation, rubbing, and hair loss in livestock1.

Argas sanchezi & Argas persicus

Poultry Tick

These ticks are common pests of chickens and turkeys, but generally do not cause serious problems except for small flocks on farms which provide wooden housing that encourages tick establishment.

Eggs are laid in crevices in the wood. All stages of these ticks remain around the roosting area of poultry, hiding in crevices during the day and generally feeding at night. Ticks can survive in empty poultry housing for years.

Argas sanchezi is a common tick of chickens, turkeys, and wild birds in California and other western states. In California it is primarily found in central valley dry climates from Shasta down to Kern county, as well as the dry coastal and inland southern California regions.

Argas persicus infests chickens mostly in the eastern U.S., and only rarely has been collected in California in Nevada County1.

Dermacentor albipictus

Winter Tick

This one host tick is found throughout North America. It is widely distributed throughout California, but populations are concentrated around the central coastal and sierra foothill areas.

It primarily feeds on horses and deer from fall through early spring. Heavy infestations of horses may cause emaciation and anemia1. After hatching from the egg, larvae attach to a host, feed and detach, remaining on the animal.

Subsequently, they molt to the nymphal stage, resume feeding and detach again. After they develop into adults and feed once again, they drop to the ground and lay their eggs, where the cycle begins once again.

Dermacentor occidentalis

Pacific Coast Tick

The Pacific Coast Tick is a three host tick which commonly feeds on rodents, especially squirrels, as subadults, and on cattle, horses, deer, and humans as adults.

This is one of the most widely distributed ticks in California. It is found throughout the state except for the very dry regions of the central valley and the southeastern desert region. The only other areas it has been collected in are Oregon and Baja, Mexico1.

Dermacentor andersoni

Rocky Mountain Wood Tick

This tick is well known as a vector of the Rocky Mountain spotted fever rickettsia in the northwestern U.S. and Canada, the Colorado tick fever virus, and the bacteria which causes tularemia (hunter’s disease). It is also commonly responsible for tick paralysis in humans, livestock, and wild mammals1.

However, in California, this tick poses little threat to human and animal health because of its scanty distribution in less populated areas of the state. It has been collected primarily in the upper eastern part of the state, from Modoc county down to the eastern range of the northern Sierras.

Dermacentor variabilis

American Dog Tick

It is the most important vector of the Rocky Mountain spotted fever rickettsia in the eastern U.S. and is also able to transmit the bacteria which causes tularemia (hunter’s disease). It has also been found responsible for tick paralysis in some states.

This tick is widespread throughout the U.S. as well as parts of Canada and Mexico. In California, it is most frequently found along the coastal ranges down the length of the state, but has also been collected in the central valley and along the eastern Sierra range1.

Ixodes pacificus

Western Black-Legged Tick

The Western black-legged tick is a three host tick that primarily feeds on lizards and small rodents during its subadult life stages, and large mammals, commonly deer, canids, horses, and humans, as adults.

It is the putative vector of the Lyme disease spirochete and the equine granulocytic ehrlichiosis rickettsia in California.

This tick is found in the western U.S. and British Columbia. In California, its distribution appears to be limited to the moister regions of the coastal and Sierra foothill ranges all along the state1.

Humans bitten by these ticks may notice intense inflammation at the site of the bite which may be slow to heal. These sores do not necessarily indicate pathogen transmission by the tick (i.e. Lyme disease “bulls eye” rash), but are frequently an artifact of irritation due to tick salivary products injected into the bite site.

Rhipicephalus sanguineus

Brown Dog Tick

This tick is the only representative of its genus in the U.S.; its cosmopolitan distribution includes temperate to tropical regions. Outside the U.S., this tick commonly infests a variety of domestic and wild mammals besides dogs.

Unlike most other hard ticks, eggs of this tick are laid inside or near housing areas of animals, in cracks and crevices, rather than outside, on the ground under vegetation.

This tick is the putative vector of the canine ehrlichiosis rickettsia and the canine babesiosis protozoa in the U.S. as well as a variety of other rickettsia worldwide.

In California, this tick has been collected almost exclusively from dog kennels scattered across the state; it is probably found in most parts of the state where dogs reside1.

References

D.E. Sonenshine. 1991. Biology of Ticks, Vol. 1. Oxford University Press, New York.

D.E. Sonenshine. 1993. Biology of Ticks, Vol. 2. Oxford University Press, New York.